Tulku Urgyen Rinpoche (1920-1996) was one of the outstanding Tibetan Buddhist teachers of his generation. Born into a family with some of the greatest masters and fascinating figures in Tibetan history, he was inspired to spend over 25 years meditating in various caves and holy places throughout Tibet.

Tulku Urgyen Rinpoche (1920-1996) was one of the outstanding Tibetan Buddhist teachers of his generation. Born into a family with some of the greatest masters and fascinating figures in Tibetan history, he was inspired to spend over 25 years meditating in various caves and holy places throughout Tibet.

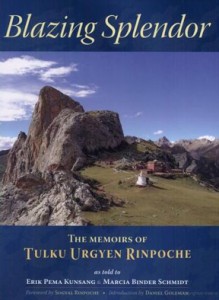

Blazing Splendor is a book of Tulku Urgyen Rinpoche’s memoirs. In this book there is a chapter entitled, “The Nunnery of Yoginis”. He tells “one story that people should definitely hear”. This story is his recollection of the Gebchak nuns and lamas when he visited Gebchak Gonpa as a boy. It provides a valuable record of Gebchak Gonpa from around the 1930s together with Tulku Urgyen Rinpoche’s extraordinary insights.

Excerpts from “The Nunnery of Yoginis”:

Tsang-Yang Gyamtso, the founder of Gebchak Gompa, had passed away long before my stay there as a child. Tsang-Yang Gyamtso had been born into an important local family and was rich, powerful, and quite arrogant. As a young man he had enjoyed hunting. In those days rifles could shoot only one bullet at a time. One day he saw a herd of deer in a valley. Taking aim, he hit a fawn. Its mother turned toward him and, letting out a pleading cry, continued to guard the rest of the herd.

As she stood there looking straight at him, Tsang-Yang began to have second thoughts, “Oh no! She knows I am going to kill her and yet she lingers there to save her fawn. I am a true murderer!”

As he reflected on this a deep sense of self-loathing welled up within him. He flung down his rifle and smashed it with a large stone. Next he threw away his knives and daggers; unleashing his horse and yak, he set them free. At a villager’s house along the way, Tsang-Yang told the owner where he had left his horse and that the man could have it.

Then he set off on foot with only one thought in mind, “I must meet Lama Tsoknyi!”

At this time the first Tsoknyi was the lama at Nangchen palace’s main temple. That morning Tsoknyi had told his attendant, “A man will probably come to meet me today, a stranger. Let me know the moment he arrives!”

At mealtime, Tsoknyi asked, “Has anyone come yet?”

The attendant replied, “No one special, just this frazzled, tired-out guy. I gave him some food and a place to rest. No one important has come, only him.”

“That’s the one!” exclaimed Tsoknyi.

“I told you to notify me right away. Bring him up here immediately.”

As soon as they met, Tsang-Yang Gyamtso said, “I have completely given up the aims of this life. Now my only goal is to practice the sacred Dharma from the core of my heart. Please accept me as your disciple.”

“Very well;” Tsoknyi replied. “If that’s what you really want, you must start from the beginning. I will teach you only if you follow my instructions while you stay in retreat.”

Tsang-Yang Gyamtso was then given a small hut on the hillside. It’s still there; I’ve seen it myself. After a while Tsoknyi told him to stay in that hut and not come back for three years. Tsang-Yang readily accepted. Noble beings make faster progress than others during a three-year retreat. The story goes that after those three years, he had attained a very high level of realization.

Tsoknyi himself was an incarnation of Ratna Lingpa, one of the major revealers of terma treasures. I was recognized as an incarnation of Chöwang Tulku, who was also one of the first Tsoknyi’s disciples.

Under Tsoknyi’s guidance, Tsang-Yang Gyamtso became an eminent practitioner. He was also very bold and intrepid. For example, once he traveled to the lower part of Kham to visit both Khyentse and Kongtrul. Upon meeting Kongtrul, he insisted on being given a complete set of the wonderful new collection of sacred scriptures that he heard Kongtrul was about to publish. Because of his audacious tenacity, Tsang-Yang was the first lama to receive a printed version of the Treasury of Precious Termas from Old Kongtrul himself.

Tsang-Yang Gyamtso became an outstanding master, and had between five and six hundred disciples who showed signs of accomplishment. These disciples themselves had innumerable disciples who were able to benefit beings in countless ways – I personally met many of them.

~~~

One day, Tsoknyi told Tsang-Yang, “Your forte in benefiting beings lies in building nunneries. Female practitioners are often not valued, and so they have a harder time finding proper guidance and instruction. Therefore, rather than keeping a congregation of monks, you should take care of nuns. That is your mission.”

Tsang-Yang followed Tsoknyi’s command and built two major nunneries, one of which had thirteen retreat centers. His benefit for beings became broader than his master’s. Most of the nuns practiced the revealed treasures of Ratna Lingpa, which include Hayagriva as well as the peaceful and wrathful deities. Each retreat center focused on a different cycle of these treasures.

…

Gebchak’s main abbey had thirty-six connected nunneries. Some of these had as many as four or five hundred nuns each, while even the smallest had about seventy. On the other side of the valley was a gompa for male tokden meditators, literally, “realized ones,” with their hair tied up on the top of their heads—many of whom actually were quite realized. But I noticed some of them covered up their lack of realization by putting on pretentious airs.

Looking down through the valley, you could see at least twenty large stupas. This entire valley was unique, but you only realized how unique when a great master was passing through. Then, as far as the eye could see, the landscape became a sea of red robes. Another time it became visible was once a year when the nuns would put up prayer flags by the thousands. When they were done and the wind blew, the entire mountain seemed to come alive.

…

The head lama had made a rule that there should be no loud talking outside. The nuns could talk to one another in a low voice. But if they wanted to call someone, they couldn’t yell. They had to clap their hands and beckon the person with a wave. Even with so many nuns living on that mountainside, I always felt it was totally quiet.

Each nun would sit in a little box about one square meter—only slightly larger than her. The boxes lined the walls, with a space in the middle, so that about sixteen nuns could reside in an average room. The program was to practice throughout day and night. Upon entering a practice center, a nun would take her seat in a box containing a stuffed mat. After that there was no more lying down—not even to sleep!

I visited these rooms, which were on average the size of my small living quarters here at Nagi. Each room would have an altar with the representations of body, speech, and mind. One or two of the senior nuns would keep the schedule. In the early hours before dawn, a gong would be rung. In the center of the room was a small hearth for keeping the teapot warm and, sometimes, the soup. There was no fixed duration for this kind of retreat, but many nuns would stay for life.

The nuns’ simple way of practice deeply impressed me. I felt it would be a meaningful way to spend one’s life.

~~~

When I was a bit older, I returned with my father to Gebchak when he was invited to teach a group of two hundred nuns who were quite adept at yoga. Whenever he taught there, in the evenings his room was always packed with fifty or more nuns asking additional questions.

Many of these nuns displayed signs of accomplishment, such as the inner heat of tummo. Once a year, on the night of the full moon of the twelfth month of the Tibetan calendar, there was a special occasion to show their mastery in the tummo practice of inner heat called “the wet sheet”. In the eight directions around the practice center nuns lit fires to melt snow where the sheets would be soaked. At this time of the year it was so cold the wet sheets would instantly freeze upon being pulled from the cauldron. Despite the bitter cold, many local people would come to witness the ceremony, often bringing their children along as well.

The nuns were naked underneath the large sheets, except for short pants. I forgot if they were wearing boots or not; they may have been barefoot. Those without any tummo experience found the cold almost unbearable; they would get stiff legs and frozen toes as the night wore on. For ordinary people it was virtually impossible to even take a few steps wearing only shorts, let alone a wet sheet.

The nuns began at midnight by singing the beautiful melody of supplication while walking one full circumambulation of the monastery complex covering the hillside, which was quite a long distance. The nuns wearing the sheets would walk slowly during the song. They were singing and asking for the blessings of Tsoknyi, Tsang-Yang and the other masters of the lineage, as they continued to circumambulate until dawn. They begin at midnight, at first the sheets are not soaked; the nuns merely walk while practicing tummo.

Halfway through the night, their sheets are lightly moistened from the water in the cauldrons and you begin to see a wisp of vapor from the heat of their tummo. Then the time would come to completely soak their sheets, immersing them longer in the cauldrons. Sometimes the vapor from the line of nuns would be like a bank of mist drifting down the mountain. You could see beads of sweat on their bodies while the rest of us were standing there shivering. I saw this with my own eyes several times. There were about eight hundred nuns participating. Of these, around two hundred had some degree of mastery in tummo; only these nuns would soak their sheets in the water cauldron.

It is incredibly inspiring and moving to watch such a procession and I haven’t heard of this happening on such a scale anywhere else in Tibet or Kham. Those nuns were quite impressive. Upon passing away, a great many of them remained in samadhi and some even left relics in their ashes.

I feel that this is one story that people should definitely hear.

Acknowledgment:

Reproduced for this website with kind permission from Rangjung Yeshe Publications. For English and Chinese versions of the entire book, please see www.rangjung.com

Schmidt, Erik Pema Kunzang and Marcia Binder Schmidt, 2005. “Chapter 16: The Nunnery of Yoginis” In Blazing Splendor: The Memoirs of the Dzogchen Yogi Tulku Urgyen Rinpoche. Compiled, translated and edited by Erik Pema Kunzang and Marcia Binder Schmidt, with Michael Tweed. Excerpts from pages, 157–62. Rangjung Yeshe Publications.